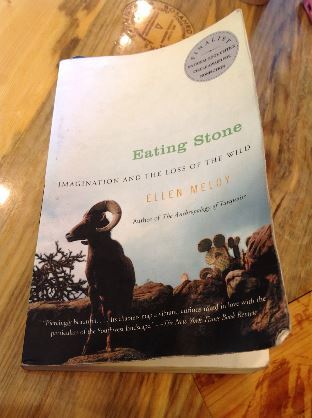

The best of books become companions, a comfort you carry and escape into during quiet moments. The late Ellen Meloy’s book, Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild (Vintage Books, 2005) has been such a friend during the first days of CFI’s 2017 season. My copy, now dog eared and worn, patiently endured soggy episodes with loose-lidded Nalgenes carelessly tossed into my pack and dusty baths on the ground while I urgently searched my bag for snacks. Grimy fingerprints dapple most pages like freckles. I do not think Meloy would mind, her writing harbors a weathered patience echoed by the condition of my copy.

In Eating Stone, Meloy deftly melds a world of astute scientific observation with the musings of her own wild imagination as she recounts her embedment with a band of Desert Bighorn Sheep. Her adventures into the wilds of New Mexico and beyond are depicted with wry humor and a nimble prose that usher the reader along in her footprints. Through her observations, the reader comes to understand the sheep as complex animals: precocious, hyper-social and intensely loyal to their native ranges. Bighorn Sheep have evolved as specialists within their environments, and Meloy marvels at the adaptations of Desert Bighorn in an inhospitable climate where it seems there is nothing to eat but rocks and where the earth is steep in every direction. On a dime, she turns to juxtapose the susceptibility of these animals to the pressures of predation, disease and of course, human encroachment on their habitat. The sheep balance precipitously between life and death, resurgence and disappearance.

Meloy’s affection for these animals is infectious, and she uses the force of this endearment to delve into what she believes is the foundational role wild animals play in human psychology. Her extensive observational notes deal as much with matters of the heart as they do with animal science. Here, Meloy delves into our own natural history in an effort to diagnose conditions of our own humanity:

The human mind is the child of primate evolution and our complex fluid interactions with environment and one another. Animals have enriched this social intelligence. They give concrete expression to thoughts and images. They carry the outside world to our inner one and back again. They helped language flower into metaphor, symbol and ritual. We once sang and danced them, made music from their skin, sinew and bone. Their stories came off our tongues. We ate them. They ate us.

Predicated on a desire to understand our society in the context of the natural world, Eating Stone caterwauls between the realms of wild and of human, illuminating the undomesticated character that lurks in our brains. In Meloy’s diagnosis of our connection between self and nature, she describes a decayed state where, our fascination with the wild is no less alive, but one where our physical connection to animals wobbles tenuously.

To illustrate this human/wild connection, Meloy draws attention to the representations of wild animals evoked in our cultural imagery. Even the coffee shop I’ve sought out to write this review, covered in a blanket of wifi, boasts a rack of greeting cards printed with a local photographer’s wildlife shots. The woman standing near my wobbly table-vantage point has the tattoo of a cartoon fox across her calf. In line at the register, a toddler clings to his mother’s pants with one hand and to a weary teddy bear in the other. Representations of wild animals are everywhere, and yet we fail to connect these images to the real thing- to the conservation of the wild resources on which our imaginations depend. Here, is a compelling, selfish, way to make the case for conservation: we aren’t human without wild spaces or the animals who cling to islands of refuge there.

For me, Meloy’s compelling call to conservation evoked the hunger with which I devoured another dog eared paperback. When I was sixteen, my dad gave me his copy of Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire; it’s binding was broken into several pieces- each in danger of being misplaced. In my teenage reading of DS, I discovered Abbey as an attractive rogue who, with his ill mannered prose, pissed on high-browed nature writing. He taunted my teenage self, desirous of more rebellion than I was willing to provoke, with his injunction to “brew your own beer; kick in your Tee Vee; kill your own beef; build your own cabin and piss off the front porch whenever you bloody well feel like it”. What both Abbey and Meloy succeed at in their writing is a searing and highly logical critique of society that forces us to question our own assumptions. A paragon of misanthropy, Abbey, however, has remained more of a nostalgic literary hero than one to emulate (though each time I see surveyor’s stakes in the ground I fight the itchy-fingered urge to toss them into the surrounding greenery).

Enter Ellen Meloy. Without hiding her dismay for the lifestyles of many of her fellow Homo sapiens, Meloy still harbors a sensitive compassion for the rest of us, sheltered in the stifling security of sprawling urban spaces. It is here that Meloy surpasses Abbey, because she doesn’t make her point by simply condemning modern society. Where Abbey sarcastically opens Desert Solitaire by imploring his readers not to go visit the places he describes in ineluctable detail, Meloy urges us to engage: “Crane your neck. Worm your way. Wolf it down. Monkey with things. Outfox your foe. Quit badgering your tax attorney. Take notes on the deafness of coral, the pea-size heart of a bat. Be meticulous. We will need these things so that we may speak.” Better to read Meloy than Abbey as I draw on reserves of patience for the parades of enthusiastic hikers who ascend and descend past our work sites on the State’s Fourteeners.

This summer, on the trails, I am inspired to aspire to Meloy’s ethos of environmentalism predicated on: careful outward observation of the natural world, honest inner reflection, and a desire to share in the magic of our wild places with all sorts of people who take to the mountains responding to some itchy urge for freedom. This book has the quiet power to shift your world view ten degrees in favor of spying on sheep as an avenue to enlightenment.