In the trail construction industry, it is common to meet a large number of individuals who found their way into this line of work through a season or two with non-profit Conservation Corps. For instance, many of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative employees cut their trail-teeth with the Rocky Mountain Youth Corps, the Southwest Conservation Corps, the Montana Conservation Corps, American Conservation Experience, and so on. These Corps all share a common goal: to engage young adults in the outdoors, produce sustainable and aesthetically pleasing trails, and help raise the next generation of environmental stewards. The word “conservation” is a word those of us in the industry hear every day, but what exactly does it mean to be a conservationist?

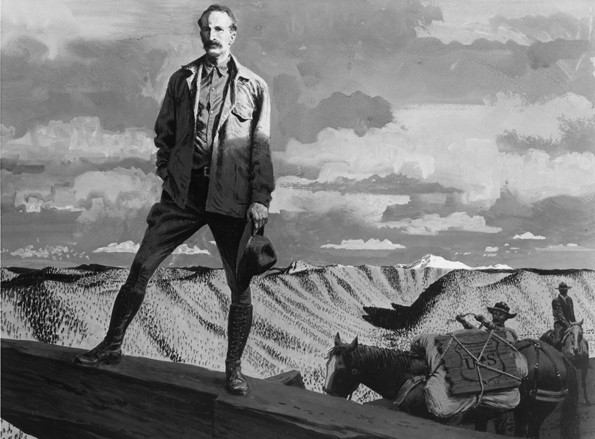

The notion of “environmental conservation” came to fruition in America at the turn of the 20th century when Gifford Pinchot, widely regarded as the father of American conservation, became the first Chief of the Forest Service (USFS) in 1905. Pinchot believed that he could use the “rhetoric of market economics” to entice the American public into acceptance of the federal government’s growing influence over the nation’s public lands. With the help of his friend President Theodore Roosevelt, Pinchot implemented his ideas of conservation, pushing to balance the protection of public lands with the economic growth created by the abundant natural resources available within the forests. Over time, the tourism created by the recreational opportunities found in the outdoors became an additional source of income for many towns. Ultimately, Pinchot’s concept of conservation stated that, with proper management, we can protect our National Forests for future generations, while also utilizing the natural resources within the forests to drive an economic engine here in the States.

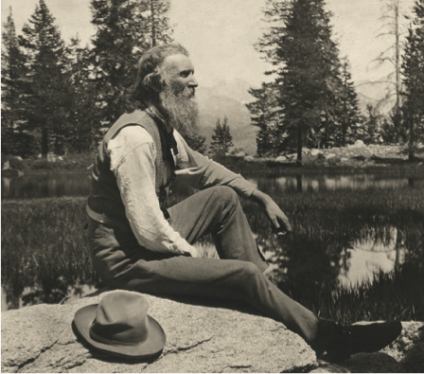

Many citizens who wanted to prevent the commercialization of America’s forests and to preserve them as they were, by eliminating or constricting human impact in certain areas, openly debated Pinchot. John Muir, the most prominent preservationist in our history, was at the forefront of the debate on how to better manage our public lands. Pinchot and Muir were at opposite ends of the spectrum between environmental conservation and preservation, and the public discourse between these two figures was well publicized, becoming a common dinner-time topic for many families at this point in American history.

Luckily, President Woodrow Wilson effectively found a compromise in 1916 when he created the National Park Service (NPS) to reside over the growing number of designated National Parks. Together the USFS and the NPS came to share the responsibility of environmental stewardship, essentially giving the USFS and the NPS each the roles of conservation and preservation, respectively.

Under the examples set by Pinchot and Muir, it is easy to see that the ideas of conservation and preservation both include a measure of protection. Environmental conservation allows for the utilization of the land in a managed and sustainable manner, while preservation purely focuses on limiting human impact on America’s wild places. It is no mistake that most of our favorite National Parks are surrounded by National Forests.

Conservation Corps strive to create a pathway for humans to enjoy much of the recreation offered in National Forests. By constructing trails that sinuously wander back and forth across ever-climbing contours, we create sustainable trails that will not erode in an unattractive fashion. This encourages hikers to remain on the trail and to limit their impact to a singular location. Trail construction is one of the many ways we aim to protect the land we serve; we build fences, plant trees, create fire-breaks, close poorly established campsites and old unsustainable trails, and more. Everything we do focuses on creating intelligent access to wild places that constrains human impact into designated locations.

In reality, I don’t think any modern conservationist would say that they are NOT a preservationist. Go search the camp of the nearest trail crew (with permission of course), and I am sure it won’t take long to find a book of John Muir’s musings, or perhaps a copy of the Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold. All good things come in moderation, so I like to think that both Gifford Pinchot and John Muir would be happy to see the balance between conservation and preservation found in the environmental stewards of our generation today.

Sources:

http://www.foresthistory.org/ASPNET/People/Pinchot/Pinchot.aspx

https://www.fs.fed.us/blogs/conservation-versus-preservation