On Mount Princeton last week, I found home in a flat clearing at the top of a private knoll of white quartz. On the outskirts of an adjacent ponderosa stand, low scrubby bristlecones have actively hunkered for hundreds of years. An adaptation that allows them to coexist within the harsh conditions of subalpine- extreme winds, heavy snows, temperamental changes that vary as much daily as seasonally. Their resilience convinces me, vulnerable human animal, that I am safe to pitch my tent among them.

One evening, I gaze out to the north, scanning the foothills of the Collegiates. I register a stillness in the tract of pine and fir. A haze looms over the town of Buena Vista in the Arkansas Valley to the northeast, Brown’s Canyon into Salida to the southeast. The backlit haze creates a layering effect on the outlines of distant peaks and ranges, like a default wallpaper on and old desktop computer. Princeton’s bald head towers directly west, over me and the krummholz crouching on its hips.

Radiating heat from glistening quartz sand and dark shards of metallic granite push me to seek refuge in the stand of ponderosa. I stand below the canopy with its soft lighting and allow my fascination to take hold. The details of living things both large and small that we often skip over in our rush to get from point A to point B.

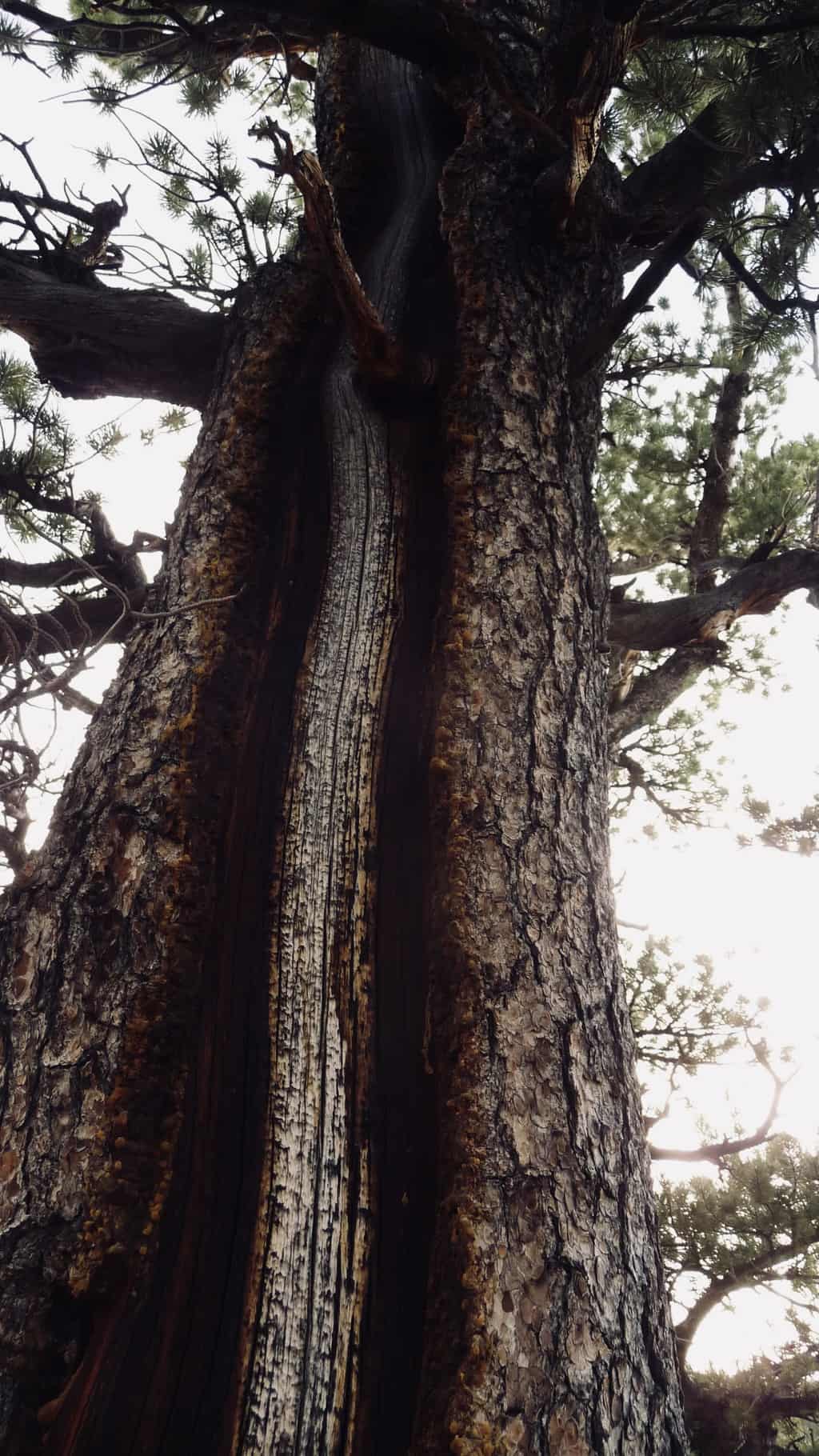

I notice a history in this particular stand of pines. The bark of individual trees are still intact, thin and flaky, albeit some charring patterns from a past fire. But on most of the trees, a strange pattern. Vertical strips peeled away from the base of the tree to the crown revealing twisted bark underneath and stripes of discoloration. I’m no naturalist- maybe someday. The patterns in the bark to me seemed strange. The edges of which glistened with golden sap.

Earlier in the day, we were warned of a potential wind storm, and I feel the beginnings blowing in from the south, carrying with it the scent of the 416 fire. Colorado wildfire season is in full swing. Human or not, wildfires are a natural phenomenon in the cycle of forest succession. A reset of sorts; An opportunity to scrub itself of overgrowth twisting around and in, evidence of decades of use, the multitudes of species who have subsisted on and within.

I head back to my tent and fall asleep quickly, muscles sore to the bone from bearing the weight of a saw, the brunt of thick logs we cut to be installed in trail to prevent erosion from hundreds of feet, both human and not. And water, coursing down the fall line of the mountain.

In the middle of the night the wind grows stronger and thrashes against the south- facing wall of my tent. I feel the wall bow low and rattle against the outside of my sleeping bag. I remember the krummholz out there and tuck my head into my sleeping bag, curl my body into itself. Up here, we make ourselves small.

On and off I wake and fall back into slumber, hovering in between the two states. The wind dies down around the tent, and you can hear it howling out and above, white noise as a sleeping aid. Then, a strong gust would threaten the integrity of my tent and I’d wake, tuck myself in further, make myself smaller.

I’m 24 years- old and have lived in a tent every summer for the past eight years.

I’ve laid awake on exposed hillsides during lightning storms, curling my body onto my sleeping pad to insulate from potential ground surge.

I’ve shivered myself to sleep on nights that formed ice crystals around the opening to my sleeping bag.

I’ve slept through wind storms like this, surely. I’m no longer afraid of the sound of heavy footsteps outside tent walls, ambling towards the kitchen. I’m only slightly afraid of the dark woodline and the sound of breaking sticks in the middle of the night when I get out of my tent to pee.

At 4:45 AM my alarm tolls the final workday before town burgers and beers. Before standing in front of a mirror minutes away from that glorious first shower (the gift of running water!). Noticing new lines of definition on skin, among patches of caked dirt and settled dust. Before it all washes off in a grey cloud that circles the drain until you turn off the shower.

I’m groggy from the night of contentious sleep, and I poke my head out of the south- facing vestibule. The horizon is clear of weather but a heavier haze has sank into the valley below, the air indicative of burning bark.

I leave my tent to start the day, nearly putting on my shoes before I remember to put on pants. Alas, I hunkered through the wind among the krummholz, learning important lessons in only my third week of working in the alpine and subalpine. Stay small [in ego and temperament]. Commit wholeheartedly to your environment. Grow as twisted, resilient upward grain, and hopefully, inspire others to do the same.